Building a Better Brick

Note: I am deeply grateful to Dee Robinson for her overall encouragement, her suggestion of this topic, and for her assistance in researching it.

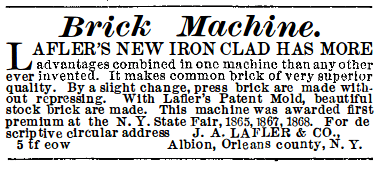

The New York State Fair, held Oct. 1-4, 1867 in Buffalo, was a disappointment in some ways. “The grounds, unfortunately, presented a rough surface—appearing as if tread up by cattle in wet weather, and left to dry and harden in that condition. The buildings were poor, unattractive, and, in some instances, of not sufficient capacity for the use for which intended….The victualing department did not present its usual attractions.”1 But for John A. Lafler of Gaines, it was a source of celebration. Along with at least two competitors, he demonstrated how his brick machine worked for the crowds at the fair, producing “crude” or unfired bricks. The New York State Fair report for 1868 noted Lafler “showed his iron clad brick machine, to which was awarded the first premium at the late fair in Buffalo, for making best quality of brick. We believe it still maintains its superiority.” Lafler not only brought his machine to the New York State Fair multiple times, but he also displayed it at the Centennial Exposition in 1876, an international event which covered over 285 acres in Philadelphia.

The only information we have about John Lafler comes from census records, his patent, a handful of passing references, and church records. Lafler first appears in Gaines on the 1855 census, but was most likely here in 1852, since his three year old son was noted as being born in Orleans County. Lafler was a native of Ontario County. When he decided to settle here in the 1850’s, Gaines had a larger population than Albion and at that point might have appeared to be a more vibrant community than our neighbor to the south. He and his family lived across the road from his brickyard which is now the Brick Pond on Rt. 98, a half mile south of Rt. 104.

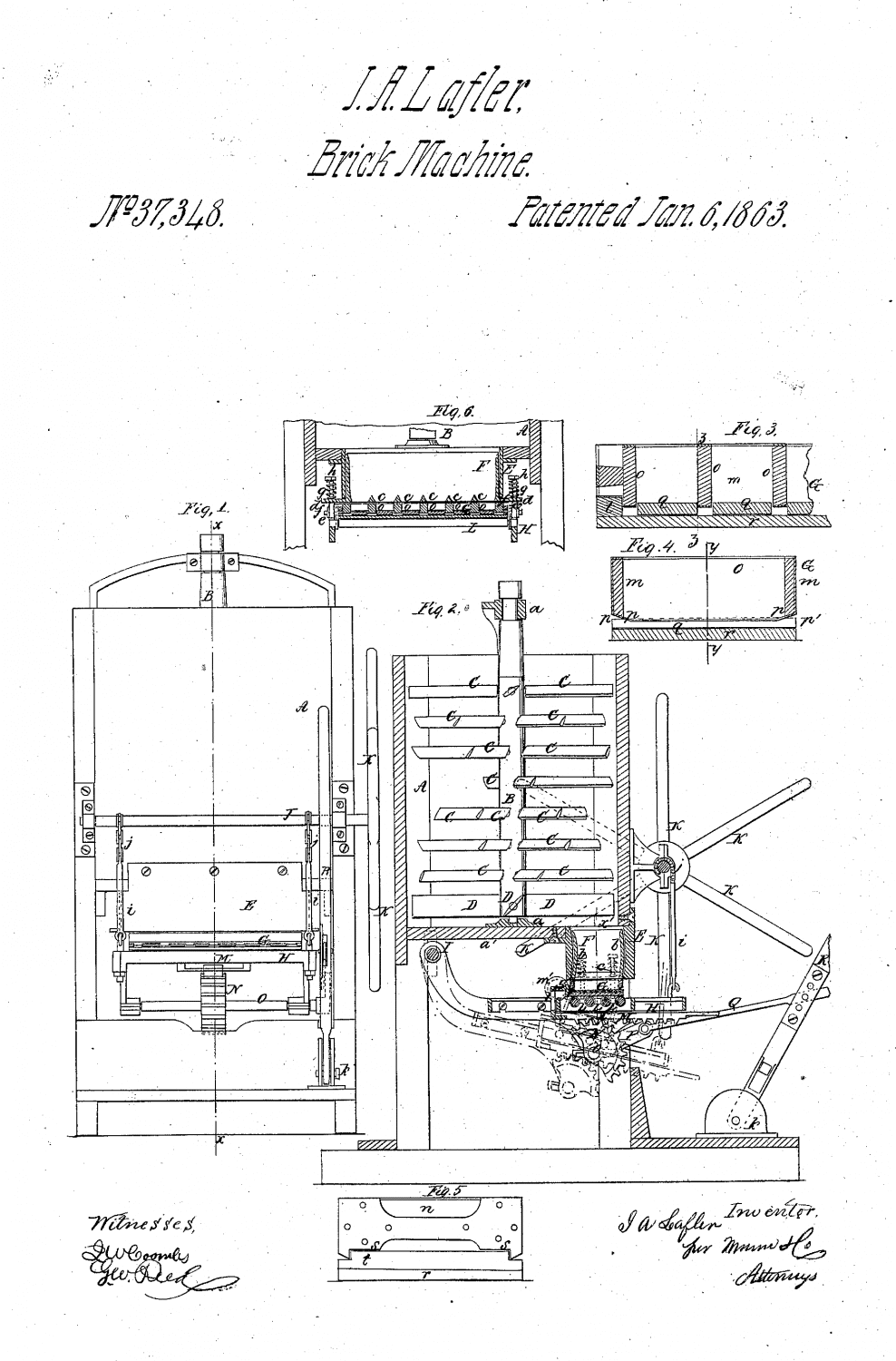

From the information we do have, we can surmise he was a successful businessman. By the time he applied for the patent for his machine in 1863 at the age of 48, he had been in Gaines for at least ten years. He enlisted the support of John N. Proctor and Isaac Gere, both from prominent area families, to sign as witnesses to his application. His brickyard was in operation from the early 1850’s to the early 1890’s. His son Charles continued to run it for over ten years after his death in 1883. As a member of the Congregational Church in Gaines, he paid for the transom window above the double doors of the old church.

Lafler’s brickmaking machine was essentially a barrel with a vertical shaft inside that had tilted blades protruding out of it. As noted in the patent, this shaft was “rotated by any convenient power,” most likely horses or steam. The clay would be placed in the barrel from the top, and the rotating blades would simultaneously knead the clay, push it down into the molds, as well as scrape excess clay off the top of the molds. A spring-loaded “clod-crusher” would compress the clay in the molds from below. It is unclear from Lafler’s patent exactly how many bricks could simultaneously be pressed by his machine. However, one of his competitors paid for a full-page advertisement in the 1866 edition of the New York State Agricultural Society’s Abstract. It claimed that the machine “will make from 2,000 to 3,000 brick per hour, with seven or eight hands and a pair of horses.” A look at the 1875 census suggests Lafler’s machine might have required a similar amount of manpower. In that year, twelve men were listed as laborers in his household, half of whom were immigrants from Germany, Ireland, Sweden, Belgium and England. It’s reasonable to suppose that if eight men were kept busy running the machine, another four might be needed to dig the clay to feed it. If Lafler’s machine had a comparable output to his competitor’s, then the amount of bricks needed to build a small brick house about the size of the one next to the Cobblestone Church in Childs could be pressed in three hours or so.

Lafler’s brickyard was not the first in Gaines. William J. Babbit established the first brickyard around 1820, on the southwest corner of the intersection of Ridge Road and Crandall Road. It is also believed there was an early brickyard on the southeast corner of the intersection at Ridge Road and Rt. 279. Before the advent of machines like Lafler’s, brickmaking in the early 19th century was a handmade, straight forward affair. Clay was pressed into a single brick mold, and then a tool was used to scrape off the excess clay. The mold was then tipped over onto a small pallet, and hopefully, the brick would come out of the mold intact. If some clay remained inside the mold, the brick would have to be repressed – the mold placed over the brick once more, tamped, and tipped out again. Perhaps this is the problem Lafler claimed his invention overcame in the ads he placed in a few 1869 issues of Scientific American.

Another improvement of machines like Lafler’s over the ages-old method of hand pressing bricks is that they would produce more uniform, more compact, harder bricks. Prior to factories, there was no way each handmade mold would each be exactly the same. Repressing would also create variation in bricks. Using a team of horses or steam power, it is easy to understand how Lafler’s spring-loaded machine would be able to exert more pressure on the clay than even the burliest of brickmakers.

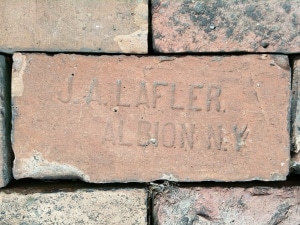

It is probable that we see Lafler’s product in many local brick houses, but we don’t have documentation. There is strong reason to believe that the First Baptist Church in Albion was constructed with Lafler’s bricks in 1858. What is now the rectory for Holy Family Parish may have also been built with his bricks as well. There is proof beyond a doubt that his bricks were used in the platform in front of the Cobblestone Church in Childs, for several have his name stamped into them.

Adrienne Kirby,

Town Historian

1The author adds, “[These faults] detracted from the visitors’ full enjoyment of pleasure, and were the source of petulant comment from some….We simply record the facts in making up a true account of the exhibition.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.