Ballots for a Divisive Election

My most sincere gratitude is extended to Donna Burdick, historian for the Town of Smithfield, and Melissa Irelan, historian for the Town of Clarendon, for their help in research.

Local history in Orleans County tends to be….local. Being rural, it’s not that we are cut off from larger currents of history, but our connections tend to be more indirect. This is certainly true in the political sphere.

On the precipice of Civil War, the election of 1860 was tense. Abraham Lincoln is often perceived as a champion of abolition, which is inaccurate. In reality, abolitionists did not favor Lincoln as a candidate because they believed he made too many concessions to proslavery advocates. Instead of voting for the “lesser of two evils,” a few men in Gaines and elsewhere in Orleans County supported the Liberty Party, which held an uncompromising abolitionist stance among other platforms outside the mainstream, such as the prohibition of alcohol.

Robert J. Anderson, ca. 1869

Robert J. Anderson (1787-1873), Gaines’ second supervisor, was a fervent abolitionist, as evidenced by the fact he was a constituent member of the Free Congregationalist Church in Gaines, and by the high probability he ran for Lieutenant Governor for the Liberty Party in 1848. In late October 1860, Robert received a letter originating from Peterboro, NY. The letter, written by Charles A. Hammond, chair of the financial committee of the Liberty Party, stated that “24 Electoral and State tickets” were enclosed for him to distribute to “hands that will deposit them in the ballot box.” The letter mentions that tickets were also sent to George Salisbury of Clarendon.

George S. Salisbury of Clarendon, NY.

George S. Salisbury (1803-1882) had the honor of having the first recorded marriage in the town book of Clarendon in 1830. He, his wife Amanda, and their eight children lived in a stone house which still stands on the east side of Fancher Rd. The Holley Standard reported in 1873 that a large number of Salisburys were members of the Good Templars, a temperance society – which is not too surprising, given his connection to the Liberty Party.

The Liberty Party ballot for 1850.

There are a number of things that have changed over the past one hundred and sixty years, and voting is one of them. In the 19th century, ballots were created by each political party and sent out to its members. In 1860, the major parties were Republicans and Democrats, but four other parties had presidential candidates as well, including the Liberty Party. State laws dictated how large the ballots could be and what sort of paper was to be used. Twenty-four “tickets,” each listing all of the candidates the party had endorsed, were printed on a single sheet of paper. Each ticket was cut out, and that is what was placed in the ballot box.

The two main contenders for the presidential election of 1860 were, of course, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas. Charles Hammond added some revealing commentary in his post script: “Let us by all means, save for freedom all we can. How can Abolitionists vote for a Slave hunting candidate, like Abraham Lincoln?” This is most likely a reference to Lincoln’s support of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which many felt was a necessary compromise to preserve the Union.

However, members of the Liberty Party by this point were also known as Radical Abolitionists. They believed in the immediate emancipation, with no recompense to slaveholders. Founded in 1840, the abolition of slavery was their primary objective, but the prohibition of alcohol emerged as a second major goal. As the 1850’s wore on, they were dismayed to see more pragmatic abolitionists shy away from absolute abolition and temperance ideals to support more nuanced approaches to these issues. As early as 1853, Charles Hammond was quoted in the New-York Daily Tribune that he “suspected the Liberty party had lost its savor, and was not worth maintaining.”

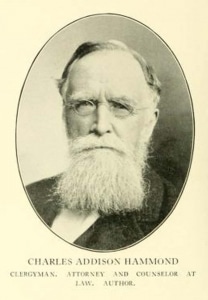

Rev. Charles A. Hammond, later in life.

Although the above reference does not indicate in exactly what way he felt the party had lost its way, one wonders if perhaps he perceived a de-emphasis of temperance ideals. Charles A. Hammond (1825-1912), both a minister and lawyer, was well-known in central New York as a vocal temperance advocate, as can be seen by numerous citations in various newspapers throughout the latter half of the 19th century. He also happened to be a friend and one-time neighbor of Gerrit Smith, a philanthropist based in Peterboro, NY, who was the Liberty Party’s presidential candidate in 1860.

Those who supported the Liberty Party in 1860 were idealists in the extreme. Had they been willing to make concessions, they might have garnered more votes, but they had a clear view of the end goal and refused to deviate from it. Over a hundred years later, Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater said, “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.”

I think Robert, George, Charles and Gerrit would have agreed.

Adrienne Kirby,

Town Historian

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.